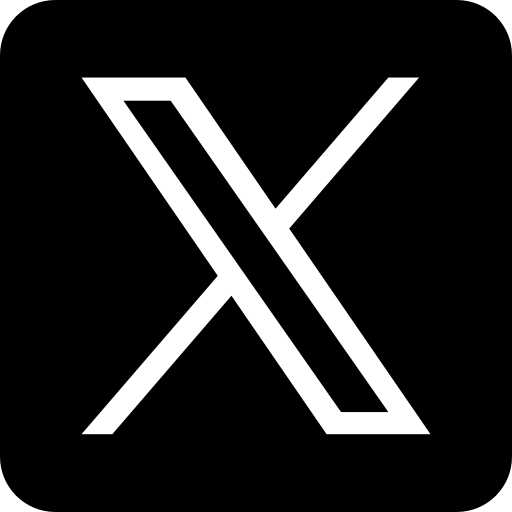

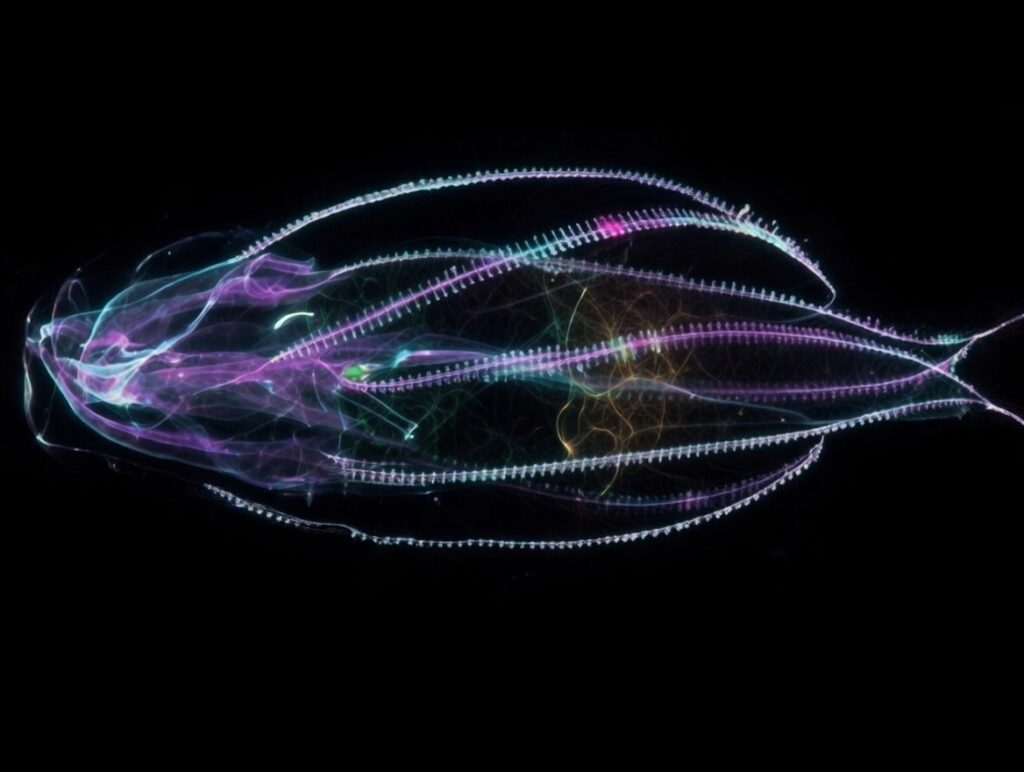

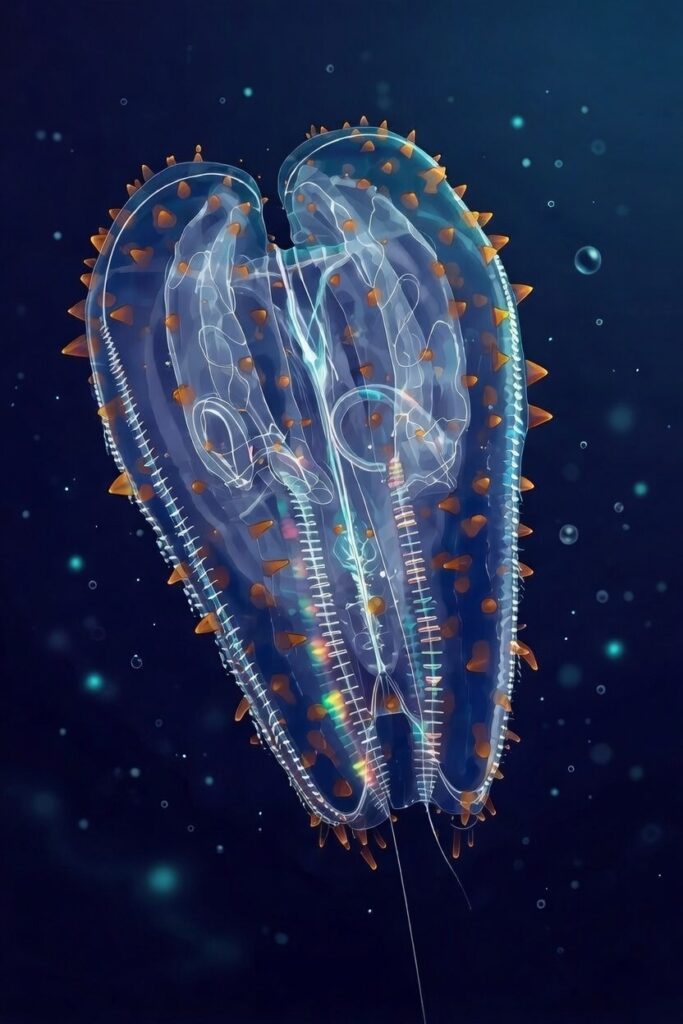

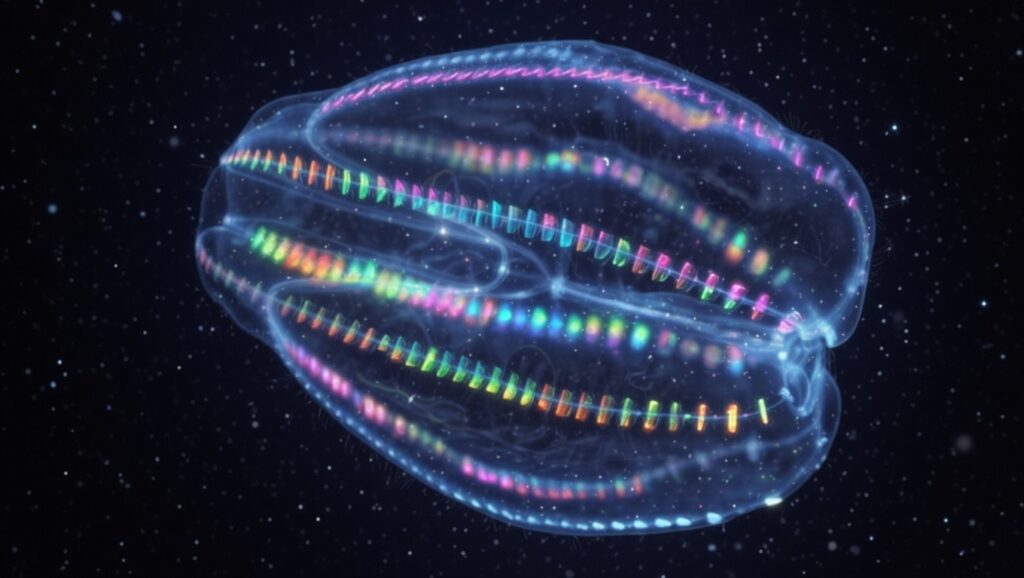

Ctenophores, commonly known as comb jellies, are among the most enigmatic and ancient animals in the ocean. Often mistaken for jellyfish due to their translucent, gelatinous bodies and drifting lifestyle, they belong to their own phylum, Ctenophora – distinct from true jellyfish in the phylum Cnidaria. These mesmerizing creatures, with rows of iridescent “combs” (ctenes) made of fused cilia that propel them through the water, have captivated scientists for their evolutionary quirks, especially in the deep sea where many species thrive in perpetual darkness. What sets ctenophores apart biologically is their extraordinary nervous system and unparalleled regenerative abilities – features that challenge long-held ideas about how nervous systems evolved and how animals repair themselves.

A Nervous System Unlike Any Other Ctenophores possess one of the most unusual nervous architectures in the animal kingdom. They lack a centralized brain in the traditional sense, but they do have a sophisticated “elementary brain” called the aboral organ (also known as the apical or statocyst organ). Located at the aboral pole (opposite the mouth), this structure includes a gravity-sensing statocyst with balancer cilia and sensory cells that detect orientation, light, and chemicals. It acts as a primitive command center, coordinating locomotion and basic behaviors.

Beyond this, ctenophores feature a diffuse nerve net spread throughout their body. Recent high-resolution studies, including 3D electron microscopy, have revealed something remarkable: parts of this subepithelial nerve net form a syncytium – a continuous, fused network of neuron membranes without the typical gaps (synapses) between cells seen in most animals. Signals can propagate directly through this fused structure, while other connections rely on conventional chemical synapses. This setup blurs the classic “neuron doctrine” (that neurons are discrete cells) and suggests ctenophores evolved their nervous system independently from other animals, possibly even twice in animal evolution overall. Some research describes ctenophores as having two morphologically and functionally distinct nervous components:

- An outer subepithelial nerve net (often syncytial in parts) handling sensory input and surface coordination.

- Deeper elements, including mesogleal neurons in the gelatinous middle layer and specialized networks around tentacles and the aboral organ.

This dual-like organization, combined with unique neurotransmitters (they rely heavily on glutamate but lack many common ones like serotonin or GABA), makes their “brain” a fascinating outlier. Deep-sea species, adapted to low-light, high-pressure environments, may leverage this efficient wiring for subtle prey detection and escape behaviors. Supercharged Regeneration: Regrowing the “Brain” in Days Perhaps even more astonishing is the ctenophores’ regenerative prowess. Many species can heal wounds rapidly and regrow entire body parts- even from tiny fragments. In lab studies, specimens like the lobate ctenophore “Mnemiopsis leidyi” (a common coastal model, though related deep-sea forms show similar traits) regenerate missing sections in days, without forming a blastema (a mass of undifferentiated cells typical in other regenerators like salamanders).The aboral organ—their elementary “brain”—can fully regenerate in as little as 3–4 days after surgical removal. Some individuals have regrown it multiple times in experiments. This process involves rapid cell proliferation at the wound site, is temporally separate from initial wound healing, and doesn’t rely on stem-cell-like reserves in the same way as other animals.

Even wilder: Injured ctenophores can fuse with others – even genetically unrelated individuals – merging tissues, digestive tracts, and nervous systems into a single functional organism. Fused animals share coordinated responses, suggesting seamless nerve integration. This ability may explain their resilience in the harsh deep sea, where injury from currents, predation, or sparse food is common. Recent findings show some species can even reverse development under stress (e.g., starvation or injury), reverting from adult to larval forms – a form of “age reversal” that resets their life cycle.

Why This Matters: From Deep Sea to Regenerative Medicine Ctenophores date back over 540 million years, predating many major animal innovations. Their independent evolution of complex traits offers clues to the origins of neurons, synapses, and regeneration. Studying them could inspire breakthroughs in nerve repair, tissue engineering, or even biohybrid systems – imagine fusing neural networks or building “neurobots” from living tissue. Deep-sea ctenophores, like those in genera such as “Bolinopsis” or rare abyssal forms, highlight how these abilities persist in extreme environments. Their bioluminescent glows and ethereal movements make them icons of ocean mystery.

In a world racing to understand regeneration for human health, these “aliens of the sea” remind us that nature solved some problems millions of years ago in ways we’re only beginning to decode. Next time you gaze at the ocean depths (or a lab tank), consider the comb jelly – not just drifting, but quietly rewriting the rules of life.

Dimitri Detchev